Original Entry: Bebop Spins

Warm up with bebop spins in 5th position and then take around the circle of 4ths.

I play from my Dharma Eye, Listen from within. Where and whenever I experience uncertainty, I engage with the moment of hesitation and train my body with my mind to completely smooth out uncertainty.

Technical Study: Bebop Scale – What the hell is it?

The “Bebop” Scale is a slightly altered Mixolydian scale that was and is frequently used to generate improvisational vocabulary for the quick chord changes that often characterize tunes composed during jazz’s “Bebop” era and forward.

Arguments could be made both for and against the usefulness of defining this scale, the “Bebop” scale, as a distinct and separate scale from a dominant or Mixolydian scale – there is only one note changing. Some teachers I have studied with swear by it, and with solid reasoning: the bebop scale is an effective way of addressing dominant chords during improvisation (though goodness, simply ADDRESSING the chords sounds so boring).

The “Bebop” scale takes a mixolydian or dominant scale – typically spelled Root, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, b7th, or rooted on C, the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, Bb – and adds one extra note, the natural 7. This note, when played relative to C turns out as a B natural. A C-bebop scale would then give us: C, D, E, F, G, A, Bb, and B natural. By making this scale, which is normally comprised of 7 notes, an 8 note scale, and interesting phenomenon emerges, one that was of extreme fascination to early players like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. And they took the idea and ran with it.

This “Bebop” treatment of a dominant scale allowed players to string together flowing lines using this scale, which by it’s nature, separates out the chord tones from the non-chord tones or passing tones. And because there are an even 8 notes instead of they typical 7, a player can start on any note of, in this example, the C7 chord – C E G or Bb – and there will always be a colorful passing tone in between each of them. This is thanks to the addition of the natural 7, or in this case, B natural, which gives us a note between the b7 of the chord (Bb) and the Root of the Scale (C). This means a player could run through the scale in 8th notes, and if they start with any chord tone on a strong beat, (beat 1, 2, 3, 4) each down beat will be a consonant chord tone and every offbeat will be a colorful passing tone.

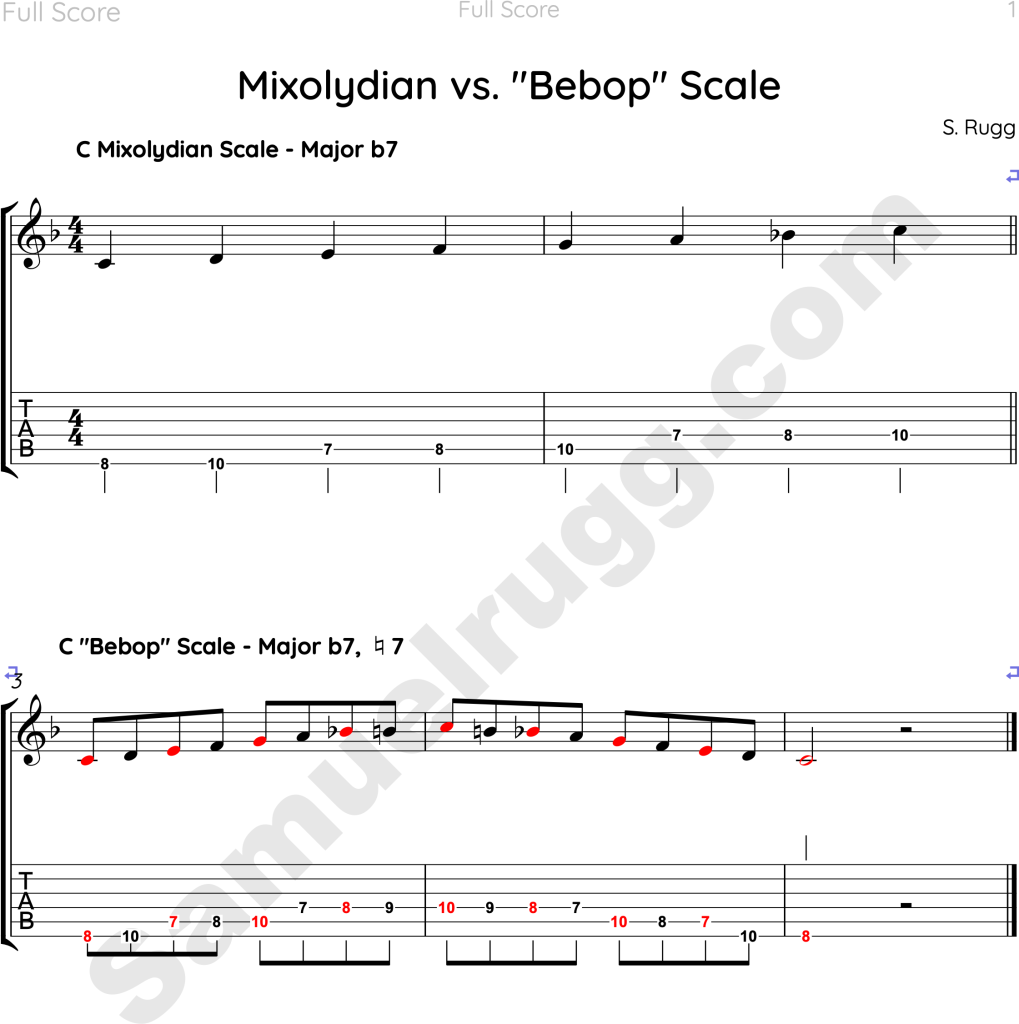

In the graphic below, you can see a few of these ideas notated out.

First, you’ll see the regular C Mixolydian scale (Major scale with a b7).

Below the Mixolydian scale, you’ll see the C bebop scale (Major Scale with a b7 and a natural 7)

You might see that the chord tones of C7 (C E G Bb), or the strong tones have been highlighted in RED. You’ll notice that these notes, when played as eighth notes, all fall on strong beats – 1, 2, 3, and 4. The passing tones have been left black – these all occur in the space between the strong beats, on the off-beats or the “&’s.”

This eight-note scale, bearing a symmetrical nature, makes it easy for players to start on strong chord tones and virtually guarantees that, if played in scalar cells, the chord tones will always fall on the strongest beats in the bar.

While some players and teachers love thinking of this altered mixolydian scale as the “Bebop Scale,” on the other hand, other teachers have expressed a marked disdain towards the over-classification of scales. It’s easy to get overwhelmed if you think of 12 major scales (at a minimum), each possessing 7 different modes (that’s 84 to keep straight, just within the major scales), pair that with Harmonic Minor and Melodic Minor in all 12 keys (and all of THEIR modes), 2 whole tone scales, and 3 diminished scales… We won’t even bother with the math on how many separate scales these permutations generate. And then adding even more scales into this proverbial pot? That sounds like a recipe for crushing undergraduate information overload.

Folks who argue against the use of distinguishing the “Bebop” scale, in my experience, have simply upheld that a player can skillfully and creatively use chromaticism in a major, minor, or melodic minor scale and achieve comparable, if not more efficient improvisational framework.

Bebop Spins

Pros and cons aside, here the scale is, existing in sound. And now, we’ve both had a chance to encounter it. I’ll send bows to my teacher for turning me on to this way of thinking, because I was quite taken with it when I first encountered the teaching; and now, I’ll offer it up to you. If it’s useful, please enjoy it, if not, you can pass on by and there is no problem.

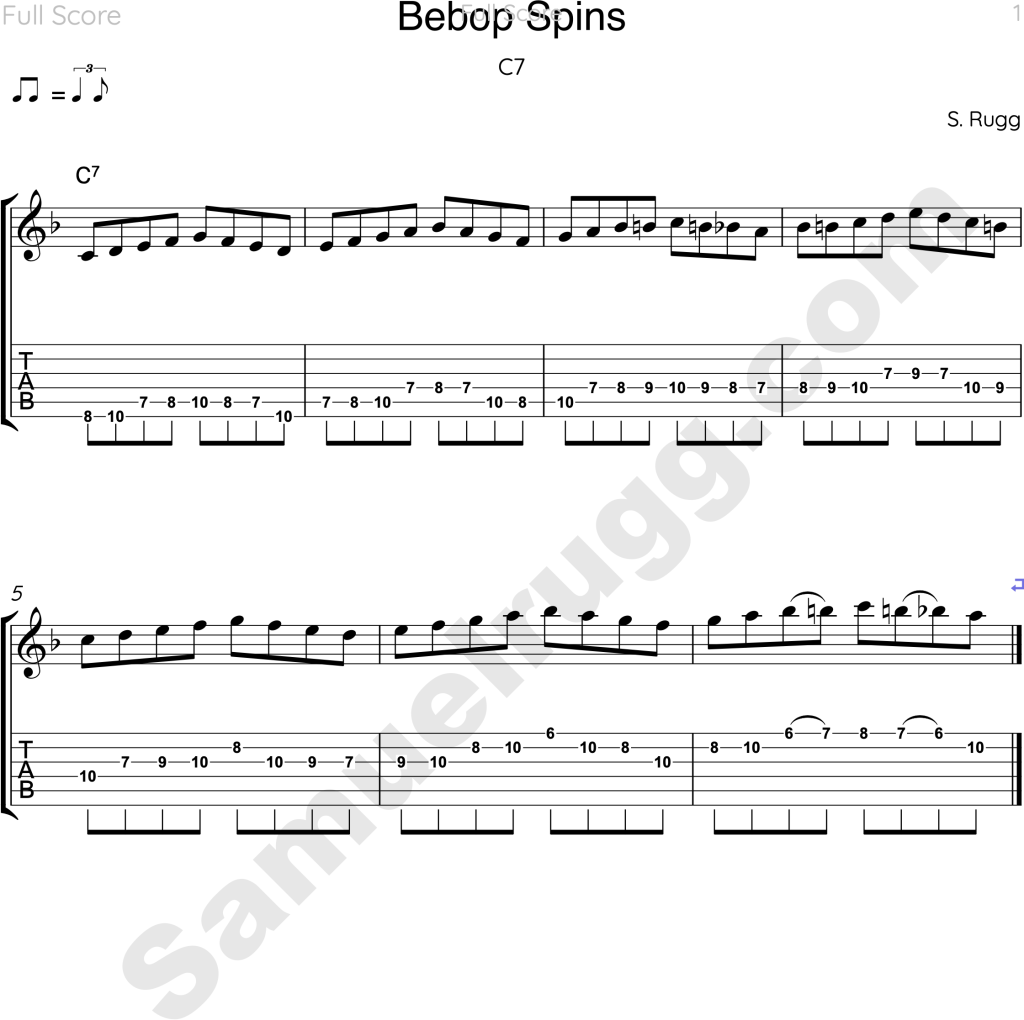

The practice that I mention in this original journal entry – of “Bebop Spins” – is built from this slightly altered dominant scale, or “Bebop” scale that we’ve been discussing. I’ve included a picture to better illustrate the process.

“Bebop Spins” are simply a scale permutation – a way to methodically arrange patterns through the notes of the scale.

Now, I talked about playing the spins in 5th position, walking through all keys. For the sake of simplicity, I’ve decided to just stick to root position, I think this will make it easier for our purposes.

So what the heck are these “Bebop Spins” anyway?.

Simply put, “bebop spins” are an easy up and down pattern that highlight the chord tones. I’ll show you.

- UP – We would start on the root, playing R,2,3,4.

- DOWN – Now, we simply start on the 5 and coming down 5, 4, 3, 2

- UP – Starting on the 3, we play up the scale 3, 4, 5, 6

- Down – b7, you guessed it, we play Descending b7, 6, 5, 4

- Up – Beginning on 5, we play 5, 6, b7, nat 7

- Down – Now we start on the ROOT, coming down R, nat 7, b7, 6

- Up – Starting on b7, we play up b7, nat7, R, 2

And so on!

You might notice a few things in this process: for one, we are always starting on a chord tone, for two, we are always alternating up and down scalar motion, for three, we are almost spinning around these chord tones. It reminds me of a monkey swinging through the branches of a tree. Sometimes I see them as little musical hinges that I can swing around.

Attached is video that illustrates the sound of this “Bebop Spin” pattern over a C7 drone!

Practice Reflection

For me, practicing an exercise like this in all keys is invaluable. If you are just encountering this idea of “Bebop spins” for the first time, I would recommend exploring this, first and foremost, in the key of C using the exercise above with a metronome, most likely in half-time, playing in quarter notes at 60 or 80. Once it gets more familiar, you can start playing with the tempo and the feel.

Once you have a sense of the shape of this pattern in C, I would recommend taking the pattern around the Circle of 4ths, simply moving the root note through the circle and copying and pasting the above pattern in the new position.

In the original post, I talk about identifying uncertainty and hesitation; I like to think of these little stumbles and mistakes as red flags. If I am stumbling over some musical moment, chances are that I need to slow down and really clarify what is happening in this moment of difficulty.

When we run into mistakes and stumbles, we often feel an energy in our body; sometimes it shows up as a feeling, other times as a thought. Regardless of how it shows up, there is usually a heat around the mistake – our expectations are not lining up with the reality of our ability, and this can lead to frustration or even full blown anger.

If you are encountering a discrepancy between your expectations and the reality of your practice, notice it. These little charges of emotional fire are actually a gift. If we can recognize that something is wrong, that things aren’t how we’d like them to be, notice that. Make a note of it. Literally, write it down. This is the fuel for your practice to deepen.

Pull out your magnifying glass, some tweezers, and break out your metronome and examine the SHIT out of the moment that is giving you trouble. Where is the mistake happening? Is it a physical thing? Left hand? Right Hand? Posture?

Or is it a mind thing? Are you loosing count? Maybe mixing up the notes? Whatever it is that is giving you trouble, I’d recommend donning your lab coat and becoming a sonic-scientist. If you can clearly identify the problem and brainstorm possible solutions, you are equipping yourself with a tool kit that will benefit your life much beyond your music or art practice.

You can practice learning.

Love and Bows

_/\_

Sam

Kogen